The UK quit the European Union on 31 January 2020, but till the end of the year the country will continue to contribute to the EU budget.

There is now a transition period until 31 December 2020 while the UK and EU negotiate additional arrangements. The current rules on trade, travel, and business for the UK and EU will continue to apply during the transition period. Therefore, the UK will continue to contribute to the EU budget until the end of the year.

As a member of the EU, the UK made payments to the EU budget and received funding from the EU for various agricultural, social, economic development and competitiveness programmes. Rebates from the EU reduced the country’s payments, correcting the issue of the UK making relatively large net contributions to the EU.

According to Eurostat, the UK was the second biggest net payer into the EU budget after Germany. Combined, these two powerhouses had a GDP (PPP) of over €5 trillion in 2018.

At the other end of the scale, Poland tops the list of net beneficiaries with a deficit of -€11,632 million—more than double that of second-place Hungary, followed by Greece, Portugal and Romania.

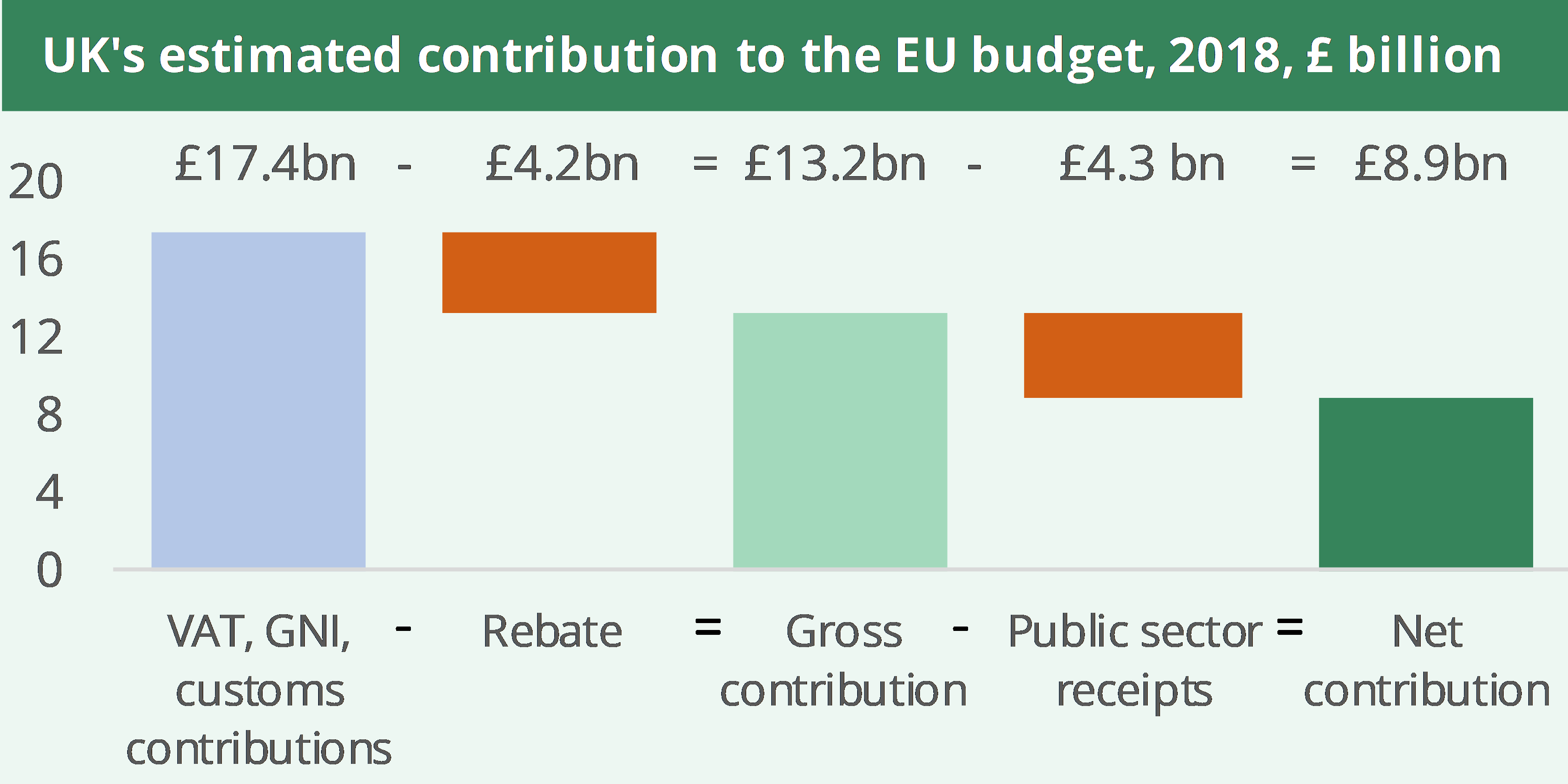

In 2018, the UK made an estimated gross contribution (after the rebate) of £13.2 billion. The UK received £4.3 billion of public sector receipts from the EU, so the UK’s net public sector contribution to the EU was an estimated £8.9 billion.

Source: House of Commons

However, the European Commission also allocated funding directly to UK organisations, often following a competitive process. In recent years, these funds were worth around £1 billion – £2 billion to the UK. Taking into account these funds, the UK made an average net contribution of £7.9 billion between 2013 and 2017.

28 countries had over €15.8 trillion in 2018 GDP (PPP). Each country pays the same proportion of its national income to the EU budget, so richer countries pay more and poorer ones less. However, some countries, such as the UK before Brexit, pay less because they receive a rebate.

When population is taken into account, the rankings of net beneficiaries and net payers shift dramatically. Per capita, the Netherlands tops the list with €284 contributed per resident, whereas Luxembourg lands in last place with a deficit of -€2,710 because the small country is home to many EU institutions, resulting in high administrative spending: in 2018, administration amounted to 80% of Luxembourg’s total expenditures.

EU revenue is broken down into four main categories:

- Value Added Tax (VAT)-Based Own Resource (2018 total: €17,600M)

- Gross National Income (GNI)-Based Own Resource (2018 total: €105,800M)

- Traditional Own Resources (2018 total: €20,200M)

- Other Revenue, including taxes on EU workers’ salaries, interest on late payments and fines, and contributions from non-EU countries to research programmes (2018 total: €15,700M)

Meanwhile, EU expenditures are broken down into six main categories:

- Smart and Inclusive Growth to boost growth, create jobs and foster economic and social cohesion through training, education, research and social policy (2018 total: €75,900M)

- Sustainable Growth: Natural Resources, financing programmes in agriculture, rural development, fisheries and climate action (2018 total: €58,000M)

- Security and Citizenship, encompassing programmes related to migration, border protection, food safety and consumer protection (2018 total: €3,100M)

- Global Europe, covering foreign policy, including international development and humanitarian aid (2018 total: €9,500M)

- Administration, including all EU institutions expenditures on staff salaries, building rent, information technology and training. (2018 total: €9,900M)

- Special Instruments to mobilize funds for unforeseen events, such as natural disasters and major world trade patterns that displace workers (2018 total: €200M)

Around 80% of the EU budget goes back to the Member States for the financing of common policies in the agricultural sector, development of poorer areas and social policies. This means that poorer countries and those with a lot of farms receive bigger funding.

The UK Government says that it may pay to participate in some EU programmes after Brexit. For instance, the UK might contribute to remain in Horizon 2020, the EU’s research and innovation programme. Exit negotiations will determine the extent and cost of the UK’s future participation in EU programmes.

A group of 15 countries who are net recipients of EU money – the so-called “Friends of Cohesion” – have lately rejected cuts to €63bn in development money in the bloc’s next budget. The EU’s net recipient countries want to freeze cohesion cash at current levels in the next budget which runs from 2021-2027.

As the EU faces a sharp funding squeeze after Brexit, Brussels has proposed to abolish the permanent rebate and increase the size of the long-term budget to 1.11 per cent of the EU’s gross national income (GNI). But five net contributors, also called the ‘Frugal Five’ countries — Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark and Sweden — have demanded a pot no larger than 1 per cent of GNI because their contributions to the EU budget are already very large.

If an agreement cannot be reached by the end of the year, spending thresholds from 2020 will be rolled over to 2021. Unless rules change, Germany is facing a steep 100 per cent increase in its payments to the next EU budget, from €15bn in 2020 to upwards of €33bn in 2027, the Financial Times reported. The Netherlands would face a rise of nearly 75 per cent, from around €7.5bn to an estimated €13bn net contribution by 2027. France would face a less dramatic increase in its net contributions, rising from about €7.5bn in 2020 to just over €10bn at the end of the spending term in 2027.

Additional reporting by Gina Isaac

Image: Brussels, Belgium / Petar Starčević

Thanks!

Our editors are notified.